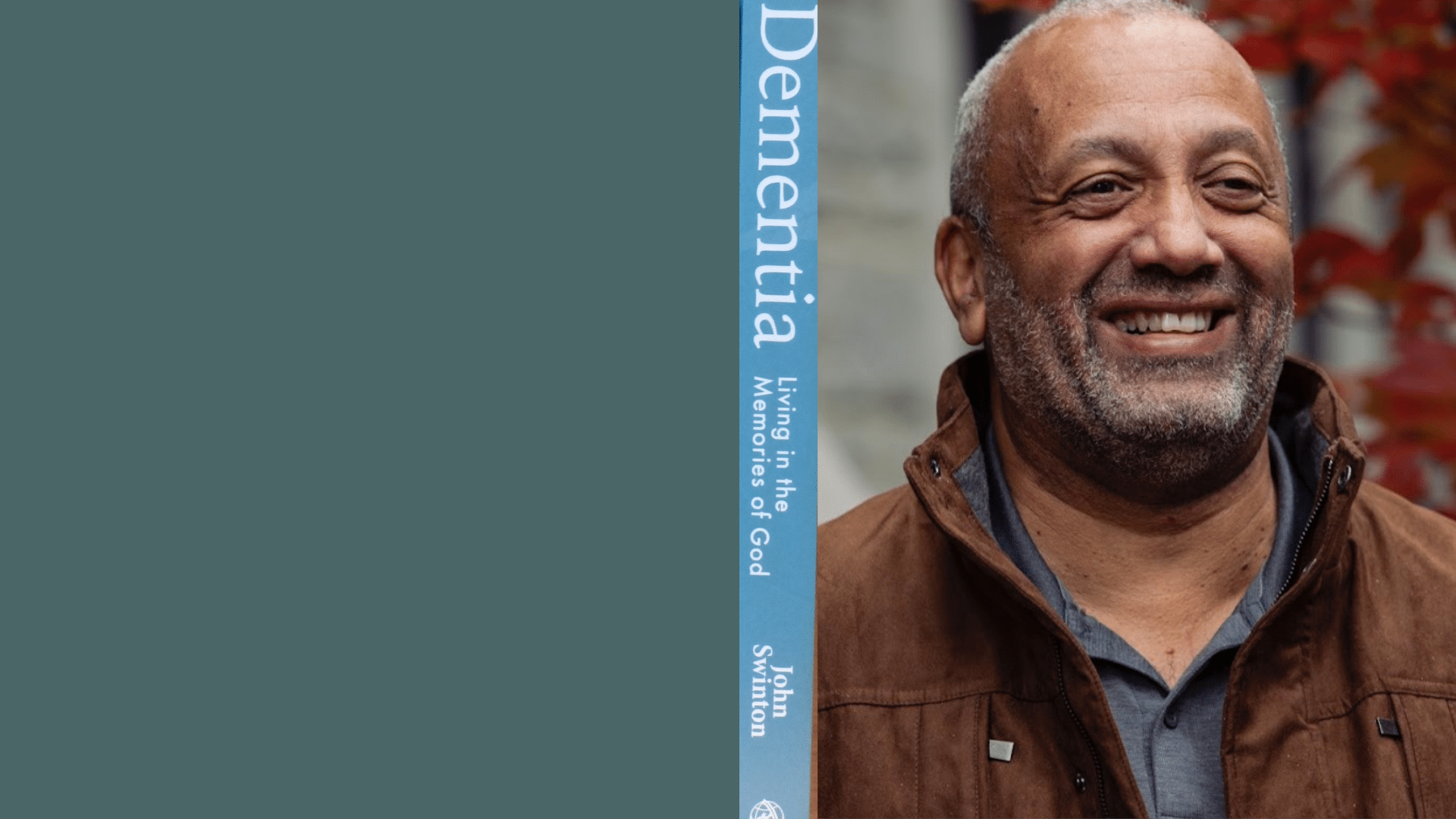

An Interview with John Swinton

Why do you think theological writing is important to the church today?

Good theology helps us to understand God and human beings more clearly in the midst of a world that constantly raises new challenges. Theological writing helps us to keep our minds focused on Jesus and to allow the transforming power of the gospel to speak into complex issues that are important for the faithfulness of the church and the future of creation. If we think of theological writing in that way, it is clear that it is of great importance for the church today.

Do you have any writing tips or advice for an early career theologian?

Don’t just follow everyone else would be my main piece of advice. The apostle Paul talks about the transformation of the mind. At least part of what he means by this is to allow the gospel narratives to shape and form our imagination in order that we can see the world differently and more faithfully. So, my advice to any theologian is to intentionally nurture a gospel imagination. By that I mean try not to be bounded or constricted by what you think may or may not be pleasing to colleagues in the academy (important as that sometimes is). Instead, allow your work to reflect the ingenuity and creativity of God and the ingenuity and creativity that God has gifted to you. Theology, at least when it is done within the academy is always a balance between the responsibilities you have to the world of scholarship, and the responsibilities you have to the calling you have been given. Not that these things are separate I hasten to add! You just have to be intentional about remembering who it is that you are trying to please. Theologians are called to enable the transformation of minds. Be prayerful, thoughtful, honest, creative and above all else, be interesting!

Can you tell us a bit more about your prize-winning book Dementia (2012). What inspired you to write it?

Before I came into academia I was a nurse in the area of mental health and learning disability. I was also a hospital chaplain for a while. In both contexts, I worked closely with people living with dementia. I was always struck by the way in which some people seemed to write them off, as if they were no longer people. It seemed that in the minds of some, damage to people’s brains equated to damage to theory personhood. When I moved into academia, the questions I encountered in my healthcare vocation, became the questions I asked of theology. “What does it mean to know and to love Jesus when you have forgotten who Jesus is?” “What does it mean to be a disciple of Jesus when you can’t remember the standard practices of liturgy, bible study and naming your friends?” “Can you lose your salvation because you have forgotten how to proclaim the gospel?” These kinds of question lie behind the book. My conclusion was simple: It is not what we remember that makes us who we are, it is the fact that God always remembers us that holds us in our identity and personhood. We are who we are in Christ, and nothing can separate us from the love of God. Nothing.

What impact has winning the Michael Ramsey Prize had for you?

Well, it helped me with my imposter syndrome! Seriously, it was lovely to have my work acknowledged in this way. I think the most important thing is that it has given the book a platform that has allowed it to enter into the lives of many people who may not have noticed it otherwise. Hopefully that has a healing gift for some.

The Michael Ramsey Prize aims to bridge the gap between popular and academic theology. What areas of theology do you think are under-addressed in popular discourse and why do you think this is?

My answer to this question is probably obvious bearing in mind my own areas of interest, but I feel that theological reflection on mental health issues is an area that needs further development. There are some excellent pieces of work emerging, but for a long time this area has been seriously underdeveloped.

Why do I think its important? Well, there are many reasons, but one important reason is that reflection on mental health, like reflection on disability draws out some crucial aspects of our humanness and what it means to live a Christian in a complex world. Take for example, the experience of depression. I don’t know how many times I have heard people living with depression lament that someone in the church told them to pray harder or spend more time reading the bible. “Christians don’t get depressed! We are called to be happy …” And yet, when we turn to Paul’s description of the fruits of the Spirit in Galatians, we quickly discover that happiness is not a fruit of the spirit. It may be an enjoyable experience, but it is not an experience that finds its primary inspiration through the Spirit. However, Paul does name joy as a fruit of the Spirit. Joy may contain the desire for happiness, but it also relate to suffering, struggle and difficult times. Jesus is our joy, but a cross centred faith recognises that, for now, our joy is not defined by the absence of suffering, but by the ways in which we can find God even in the midst of suffering.

The psalms of lament run along similar lines. They express our suffering, our doubts, our worries and allow us to take these to God. So, within Scripture there is a language of faithful sadness that even allows us to articulate our sense of being disconnected from God (“Darkness is my only companion … Psalm 88”). Mental health is of course important at a pastoral level. But when we get into the issues that are raised, we can see that it pushes us to reflect on issues that are at the heart of our faith.

Is there a book (or books!) that you have read recently which you would recommend?

There are two books that I have read recently that have been worthy of recommendation. The first is Susan Eastman’s Paul and the Person: Reframing Paul’s anthropology. It’s a really interesting reflection on the contrast between how Paul understands human beings, and the ways in which contemporary Western understandings of persons as individuals who are free, autonomous, choice seeking beings has come to be assumed as the norm. For Paul human beings are deeply interconnected. We are who we are in Christ and with one another. Human bodies are bridges that are meant to connect with other bridges. It’s a fascinating insight into Paul’s anthropology, and a powerful critique of contemporary ways of thinking about persons.

The second book is by a North American indigenous scholar Randy Woodley – Indigenous theology and the Western World: A decolonized approach to Christian doctrine. In it Woodley lays out the ways in which theology has tended to assume the primacy of Western culture and to reach out, judge and try to transform other cultures and perspectives in the light of its own enculturated view. The problem of course is that Europeans tend not to notice that their perspective ins culturally bound. This is so with many things, but it is also the case with regard to theology. Woodley offers a really interesting critique of the ways in which we do theology and offers indigenous perspectives as ways of accessing aspects of God, faith and the world which have become opaque because to the ways in which we have assumed theology to be and how it should be done.

*Please note that the views expressed in these interviews are those of the authors themselves and do not represent the Michael Ramsey Prize or the Archbishop of Canterbury.