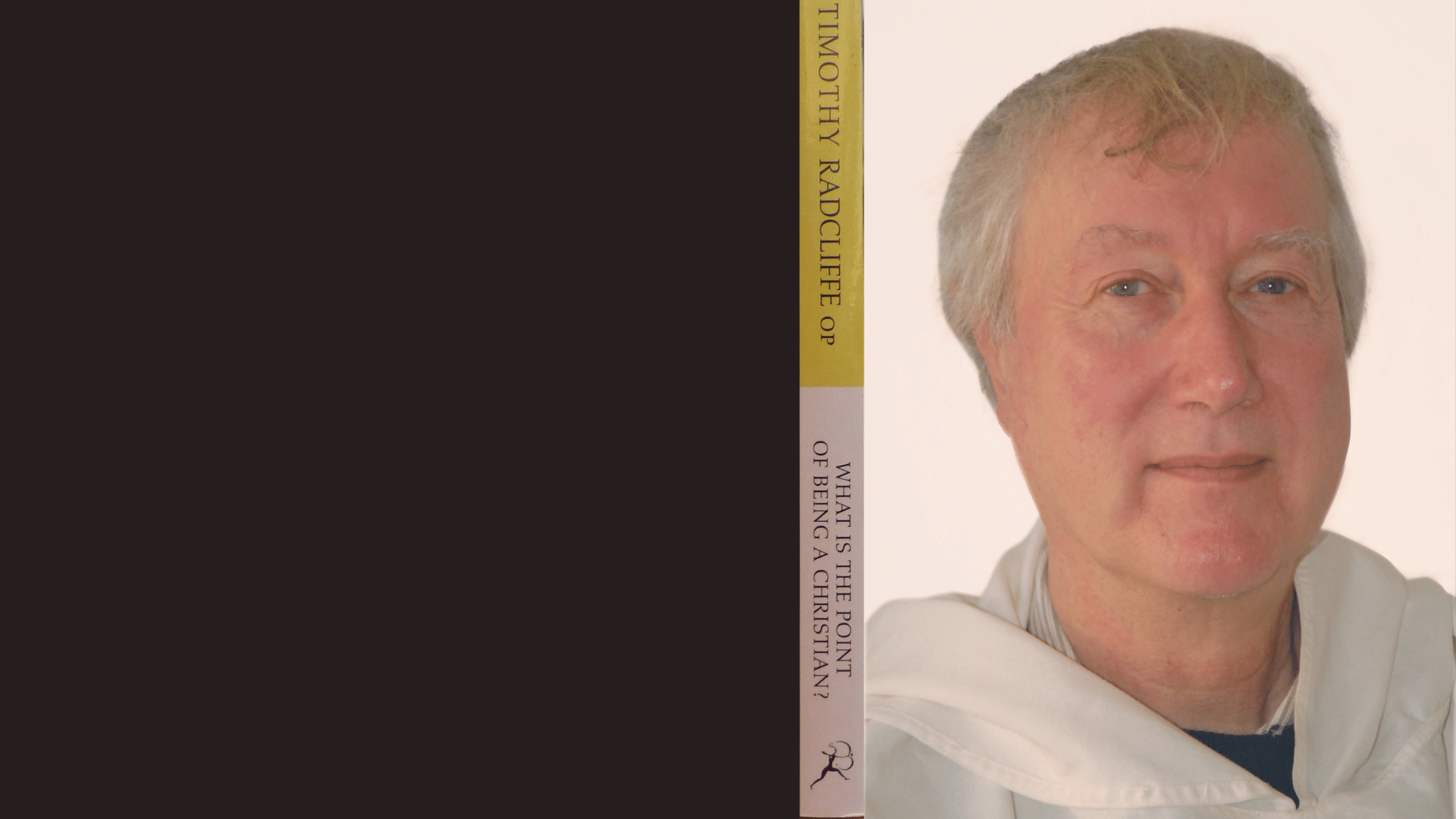

An Interview with Timothy Radcliffe

Why do you think theological writing is important to the church today?

Many young people are understandably living through a crisis of hope, with the impression that they belong to ‘the Last Generation.’ What lies ahead is deeply threatening: ecological catastrophe, the threat of nuclear war, millions fleeing poverty and growing violence, the loss of confidence in democracy. The list is long! Despair is more than pessimism. It is a sense that one’s life has lost all meaning, that nothing makes sense. So the theological task is always a search to understand what we live in the light of the promise of the gospel. It is a search for meaning, and ultimately that plenitude of meaning which can only be glimpsed at the edge of language, God.

Do you have any writing tips or advice for an early career theologian?

Be in touch with the creative people of our time, the artists, thinkers, poets, everyone who has the courage to wrestle with the questions of today. It does not matter whether they are believers of any faith or not. God’s creative Spirit is at work in their search. As Aquinas taught: if it is true, it is from God. If we are open to learn from them, they may be drawn to learn from us.

Can you tell us a bit more about your prize-winning book What is the Point of Being a Christian? (Bloomsbury Continuum, 2005). What inspired you to write it?

At dinner – in a Turkish restaurant I think! – a friend of mine who was a committed Christian said that his son kept returning to the question ‘What is the point of being a Christian? What do you get out of it? Why carry on?’ So I felt that I ought to write with this young man, whom I had never met, in mind. A few years later, my friend told me that his son had enjoyed the book, but then posed another question: ‘But why bother to go to Church?’ Another book! My friend then died and so I never heard if his son had any more questions!

What impact has winning the Michael Ramsey Prize had for you?

When I have been introduced before giving a lecture, some people have slightly irritated me by describing me as a writer of spirituality! As a young Dominican, we were formed to have doubts about anything that could be called ‘spirituality’ divorced from theology and all the ways in which people wrestle with meaning. As my Dominican master, Cornelius Ernst, taught us: theology is the meeting of the gospel and the world in a moment of mutual illumination. The winning of this prize for theological writing was important for me because it was an affirmation that what I was writing was not to be dismissed as vacuous spirituality! It also means an enormous amount to me that the jury was presided over by Archbishop Rowan Williams, a theologian and poet for whom I have the highest respect and affection.

The Michael Ramsey Prize aims to bridge the gap between popular and academic theology. What areas of theology do you think are under-addressed in popular discourse and why do you think this is?

Our society has a dogmatic stance against dogma and so people are happy to engage with spirituality, but are often suspicious of the great dogmas of Christianity: the divinity of Christ, the Trinity and so on. It is feared that dogmas close the mind and deny us freedom of thought. I believe this to be deeply mistaken. The dogmatic teachings of the Church – the Creed above all– invite us into the unending adventure of exploring the mystery of God and liberate us from small minded interpretations of our faith. So you can see why I so dislike being thought of as a “spiritual” writer! So we need brave, demanding books which explore the teachings of Christianity, the strong meat of belief.

Is there a book (or books!) that you have read recently which you would recommend?

Tom Holland’s Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (Little, Brown 2019) is a fascinating book that I must reread. It shows how strange and novel were the teachings of Christianity and how they continue to shape Western culture.

What are some books (of any genre) you regularly reread and why?

I love novels and rarely go to sleep without reading one. Charles Dickens has been a favourite since I was a child. I also love the historical fiction of Patrick O’Brian, the Aubrey Maturin novels, set in the naval wars at the beginning of the nineteenth century. I find them a fascinating exploration of an improbable friendship. It may even help me to think about what is central to my faith, the utterly impossible friendship of God and humanity. Above all I reread them because they are enormous fun and beautifully written.

Your recent book Questioning God (Bloomsbury Continuum, 2023) is a dialogue between yourself and Lukasz Popko exploring the questioning conversations people have with God in the Bible.

Could you tell us a bit about this book, and how your theological thinking has developed since you won the Michael Ramsey Prize?

Just before Covid struck, I stayed in our Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem for a month. I was hoping to update my New Testament scholarship, but the brother whom I expected would guide me was ill and unable to come back from the United States. I struck up a friendship with Lukasz, who teaches the Old Testament there and we found that we both enjoyed discussing the scriptures. After I was struck down for months by cancer, I needed a project to stimulate me and get back to something like normal life. And so the idea came to us to write this book together, and that it should be enjoyable.

Since writing that earlier book which won the prize, I have become ever more concerned with how we can touch the imagination of contemporaries. How can we excite them with the perilous adventure of faith? This led to Alive in God: a Christian imagination (Bloomsbury 2019) and surfaces again and again in this most recent book. The disciples on the way to Emmaus listened to Jesus’ exposition of the Scriptures, and their hearts burned within them. How can we communicate something of their delight?

*Please note that the views expressed in these interviews are those of the authors themselves and do not represent the Michael Ramsey Prize or the Archbishop of Canterbury.